Intercultural communication: Avoiding conflicts in the daycare center

Guide for educators on intercultural communication. Understanding communication errors, interference problems, and cultural influences in everyday childcare settings. Grosch and Leenen.

SOCIAL & VALUES

Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication is indispensable in today's world. Especially as an educator, one frequently encounters different cultures, and this can quickly lead to communication problems. It is important to know that usually it is not the original reason for the conversation that causes a conflict, but rather problems in intercultural communication that lead to misunderstandings, which then trigger arguments.

Example: An educator wants to tell a parent from an African family, who has been living in Germany for two years, that they should please drop off their child on time in the morning. The educator's reason is related to the smooth running of the daycare center. However, the parent might misunderstand the statement due to their different cultural background. This is due to different cultural influences from the past.

To delve deeper into intercultural communication, one must have a basic understanding of communication. Communication involves various levels, which are divided into verbal (pronunciation) and nonverbal (e.g., facial expressions, gestures) areas. So-called receptive and productive skills are also fundamental prerequisites for communication. While receptive skills encompass listening and reading, productive skills involve speaking and writing. Referring to the model by Schulz von Thun, there are further areas that affect intercultural communication. These include the levels of the information and relationship functions, as well as the expression and appeal functions.

A fundamental problem, especially in intercultural communication, therefore lies in the misinterpretation and misjudgment of the other person's behavior. Due to different experiences and cultural conditioning, there are differences between the communicating individuals, as each person organizes and stores experiences and knowledge in their brain in a culture-dependent way. Such communication problems are referred to in technical jargon as interference problems. (cf. Grosch and Leenen 2000, pp. 31ff)

Intercultural Competence

Intercultural competence is necessary to ensure smooth and effective intercultural communication. It helps to overcome misunderstandings, resentments, and ethnocentrism. Intercultural learning always aims to enable communication partners to act appropriately and effectively in intercultural communication.

But which areas does intercultural competence encompass, and how do I interact with my communication partner within an intercultural dialogue? Basically, intercultural communication touches upon four dimensions:

Supportive attitudes

Cultural knowledge & intercultural skills

Reflection on intercultural issues

Constructive interaction

The personal attitude towards interculturality fundamentally determines how much a person engages with the topic and thus acquires new knowledge. Respecting the other culture, which usually has different attitudes and norms, belongs to the dimension of constructive interaction, which aims to protect cultural rules. Self-reflection after intercultural dialogues and situations increases the likelihood of improving intercultural competence.

It is important to know that every situation and every contact can evoke both positive and negative experiences, which affect and influence the dimensions mentioned above. Therefore, intercultural competence is a lifelong process that is constantly evolving and will never be completed. (cf. Boecker and Ulama 2008)

Intercultural competence can be achieved through intercultural learning, with the goal of enabling smooth communication across cultures. (cf. Grosch and Leenen 2000, p. 29)

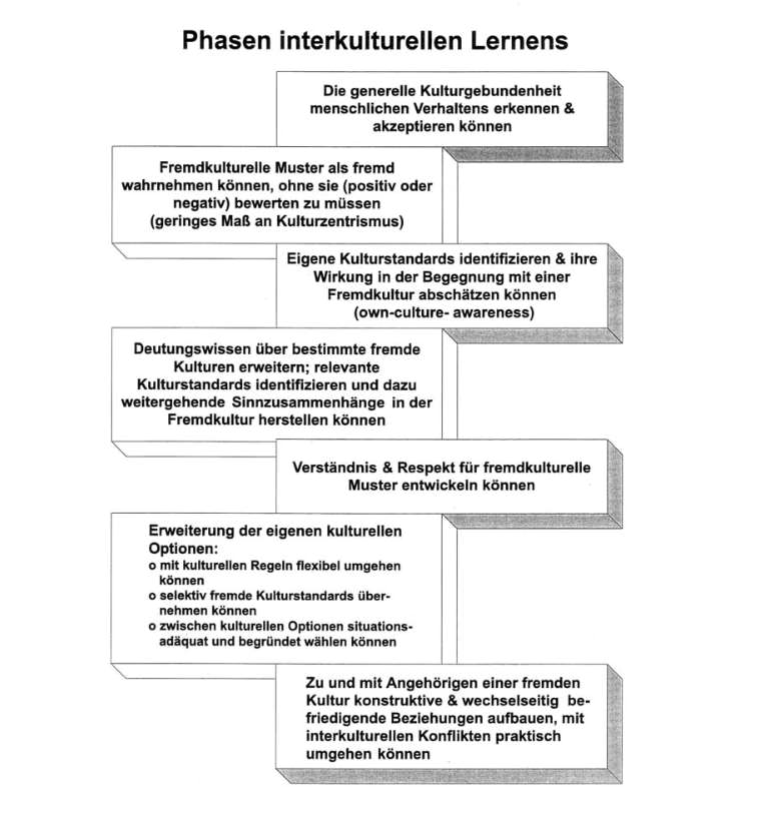

In order to achieve the goal of intercultural competence, there is, for example, a 7-phase model of intercultural learning developed by Harald Grosch and Wolf Rainer Leenen, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Intercultural Learning According to Grosch and Leenen

The 7-phase model by Grosch and Leenen is a detailed model of intercultural learning and is based on the so-called ethnocentrism theory. The phases of the model are sequential, meaning that phase 1 must be completed before moving on to the other phases. The model does not account for any disruptions or interruptions during the intercultural learning process. Throughout the learning process, the individual acquires new skills to improve intercultural communication. These skills increase from phase to phase. (cf. Schulze 2010, pp. 5ff)

After completing the learning process, the individual has acquired the ability to enter into "constructive and mutually satisfying relationships" (Grosch/Leenen 1998, p. 40).

The individual phases according to Grosch and Leenen are shown below:

The 7 Phases of the Model according to Grosch and Leenen

Phase 1

Original statement: Being able to recognize and accept the general cultural dependence of human behavior

Meaning: Recognizing and accepting a person's cultural characteristics and desires, even if you don't like them yourself. Example: The other person in the conversation listens to Balkan music. I don't like it myself, but I accept their taste in music, since they come from the Balkans and probably associate it with their homeland.

Phase 2

Original statement: Being able to perceive foreign cultural patterns as foreign without having to evaluate them (positively or negatively) (low degree of ethnocentrism)

Meaning: A Japanese person comes from a different culture than a person who grew up in German culture. The Japanese person is hesitant to address problems directly due to their culture. A German person recognizes this behavior but does not evaluate it positively or negatively.

Phase 3

Original statement: Being able to identify one's own cultural standards and assess their effect in encounters with a foreign culture (own-culture-awareness)

Meaning: Germans, for example, react differently to jokes or small deceptions than people who grew up in other cultural circles. For them, these actions can have a completely different meaning. In Phase III, a person can recognize their own cultural standards and assess the likely effect on the other person.

Phase 4

Original statement: Expanding interpretive knowledge about specific foreign cultures; identifying relevant cultural standards and being able to establish further contextual connections within the foreign culture

Meaning: In Phase IV, a person questions why something in the other culture is the way it is. This allows the person to recognize a larger context in order to better understand the other culture.

Phase 5

Original statement: Being able to develop understanding and respect for foreign cultural patterns

Meaning: A person in Phase V develops understanding and respect for patterns that a person possesses due to their different culture. These can be, for example, different patterns in communication or behavior.

Phase 6

Original statement: Expanding one's own cultural options:

being able to deal flexibly with cultural rules

being able to selectively adopt foreign cultural standards

being able to choose between cultural options in a situationally appropriate and reasoned manner

Meaning: During intercultural communication, in Phase VI, a person selectively adopts foreign cultural standards or chooses different options depending on the situation in order to achieve the goals of intercultural communication.

Phase 7

Original statement: Building constructive and mutually satisfying relationships with members of a foreign culture, being able to deal practically with intercultural conflicts

Meaning: A person in Phase VII of the model can react constructively and situationally during intercultural communication, so that both conversation partners build a satisfying relationship. The person also now deals practically with conflicts and resolves them.

Sources

Boecker, Malte; Ulama, Leila (2008): Intercultural Competence - The Key Competence in the 21st Century? Bertelsmann Foundation and Fondazione Cariplo.

Grosch, Harald; Leenen, Wolf Rainer (2000): Intercultural Learning. Working aids for political education. 2nd edition. Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education.

Schulze, Annegret (2010): Stage and Phase Models of Intercultural Learning. A critical examination of three models for the analysis of intercultural learning in the film "Stranger Friend". Munich: GRIN Verlag GmbH.