Exercise construction site: planning, goals and implementation in the nursery

How to plan a movement workshop as a holistic offering. Includes detailed factual analysis on movement, psychomotor skills and a step-by-step plan for practical implementation.

MOVEMENT & BODY

Exercise, play and fun play an important role in child development. Not only do they contribute to healthy physical development, they also support children's cognitive, social and emotional development. Through exercise and play, children can improve their motor skills, train their coordination and sense of balance, and build muscle strength in a playful way. In addition, concentration and attention are promoted during play in order to achieve tasks and goals. Children can also develop their creativity and imagination by putting themselves in different roles and situations.

Overall, exercise and play contribute to the holistic development of children and should therefore have a firm place in any child-friendly education and upbringing. One possible educational activity for these areas is a movement construction site. This gives children the opportunity to move freely and independently, overcome obstacles and test their physical limits. In doing so, they can improve their coordination, balance and dexterity, and do so together.

Using the Kuno Beller observation method, the educational activity ‘movement construction site’ was planned and implemented for a child. An analysis and description of the child was carried out. You can find this in the following article! The objectives of the educational programme were also defined. This was followed by the planning of the programme and a comprehensive analysis of the subject matter. This programme serves as a basis for similar educational activities with children in the areas of movement and collaborative play among children. Learn more about the scientific perspectives and gain fundamental knowledge.

I hope you enjoy discovering this wonderful topic and that you too will want to learn more about movement and the movement construction site in the future.

Detailed description of all areas of development

Emotional-social development

X. usually plays alongside other children during free play and does not participate in activities with other children. She does not cooperate with other children when playing together. X. finds it difficult to pick up on the feelings and moods of other children and to reflect on them further (a child falls down and cries; X. asks who is crying and then continues playing). X. is unable to assign feelings to different occasions (joy at receiving a gift or sadness at being pushed). Furthermore, X. does not imitate stereotypical behaviours. Nevertheless, she can express sympathy as well as likes and dislikes towards other people. X. also shows a partial preference for one or more children. Sometimes X. also enjoys making others happy. She tries to regulate emotions such as anger and rage. She also talks about her fears and other emotions such as joy (I'm happy because we're going to the fair at the weekend). X. also recognises herself in the mirror and in photos. However, she does not use ‘I’ when referring to herself.

In the professional-child relationship, X. needs a lot of attention and affection. In many activities, she needs the professional as a secure base and finds it difficult to engage in exploratory behaviour. X. also finds it difficult to respond to task assignments, rules and requests. In this area, X. can often only be guided by giving her attention or withdrawing attention.

Language development

X. accompanies her free play with clear statements. She can form grammatically correct sentences and express them in a comprehensible manner, meaning she no longer uses baby talk. When recounting experiences or the past weekend, X. uses the correct tense. The pronunciation and comprehensibility of words and numbers are always clear. X. can also use comparative forms of adjectives correctly. X. also uses prepositions such as “above” and “below” correctly. However, as soon as other children are nearby, verbal expressions decrease significantly. X. is not in a bilingual situation.

Cognitive development

It is important to anticipate all areas of development, especially cognitive development. X. has severe visual impairments and is therefore almost blind. This challenge accordingly accompanies her cognitive development.

During free play, X. follows ‘verbal step-by-step instructions’, for example when playing in the play kitchen. She can express abstract quantities in numbers (there are definitely 100 pictures in there...) and put together puzzles with up to 35 pieces. However, this requires the use of an image magnification device.

X. knows the function of everyday objects. She can identify the days of the week and the seasons of summer and winter. During morning circle time, she can correctly identify weather conditions such as sun or rain. When playing hide and seek under a blanket, X. can remember and guess up to two objects (observation during open activities).

At lunchtime, X. fetches the necessary materials (plate, glass, fork) autonomously when asked. X.'s ability to assert herself in terms of ‘being able to stand her ground’ is very limited (she does not seek conflict and usually withdraws from conflict situations). X. cannot correctly recognise the basic colours (except cyan and magenta).

Motor development

Fine motor skills

In terms of fine motor skills, X. sticks pieces of paper onto a sheet of paper to create a pattern of her own invention. She imitates writing and paints with a brush and paint. X. also turns over memory cards using a pincer grip. During free play, X. can be observed building tall towers or playing with various building blocks. X. is able to pour water into different containers without spilling it. She can also pick up objects from the floor with one hand. X. is unable to use scissors correctly or hold a pen correctly. She can stabilise a small stone with two fingers. At lunchtime, X. eats with a fork in an incorrect posture.

Gross motor skills

X. influences her pace arbitrarily and also changes it quickly when moving. She goes up and down stairs with alternating steps. She walks confidently along an upturned gymnastics bench using one hand. Her lack of visual performance plays a major role here, as X. lacks self-confidence rather than gross motor skills to master the upturned gymnastics bench on her own. X. also only jumps down with both feet to a limited extent. This also applies to balancing on one leg. X. throws a small ball forward with momentum.

Interests and topics of interest to the child

X.'s interests are difficult to identify with certainty. X. likes movement, but only in a safe and familiar environment. Unfortunately, the interdisciplinary team is currently unable to identify any topics of interest to X. Nevertheless, it can be said that X. is currently very much in the ‘why’ phase.

Objectives of the programme

Identification of educational and developmental areas

During the targeted programme, almost all educational and developmental areas are covered, including ‘body’, ‘thinking’, senses, ‘feelings and empathy’, ‘language’ and areas of the educational and developmental field ‘meaning, values and religion’. However, due to the planned type of programme (movement construction site), mainly and increasingly the areas of ‘thinking’, “senses” and ‘body’ are addressed.

These educational and developmental areas of the Baden-Württemberg orientation plan mentioned above are derived from the following educational areas:

Body, health and nutrition: Exploring the world using the senses.

Movement: Body awareness & experience, self-awareness; movement.

Mathematical education: Through sorting & classifying objects as well as organising & shape recognition.

Social, cultural and intercultural education: Engaging in social interaction processes and learning about other people's opinions and ideas.

Language and communication: Interpersonal verbal & non-verbal communication, dialogues.

Scientific and technical education: Learning about technology and laws of nature by discovering and exploring the environment.

The educational and developmental area of SENSES is addressed through discovery and exploration of the movement construction site. This allows children to perceive a wide variety of sensory impressions. They discover that the world can be perceived and changed in many different ways. The topic of the child (social contacts) also finds points of contact here (experiencing self-confidence, world knowledge and social contacts through sensory perception). This area of development has the following appropriate goals:

Children develop, sharpen and train their senses

Experience the importance and achievements of the senses

Experience self-confidence, world knowledge and social contacts through sensory perception...

Are able to focus their attention and protect themselves from sensory overload

Develop a variety of ways to express their ideas aesthetically and artistically

Acquire orientation and creative skills through the differentiated development and use of their own senses.

(cf. Baden-Württemberg, 2016, p. 123)

In the education and development area of THINKING, children expand their knowledge through targeted activities. There is also a strong cognitive challenge, as children have to think about possible construction options and consider holistic ideas (movement, where to? how strong, etc.). In the Thinking field of education and development, there is also the goal of children enjoying thinking together. This field of development also refers to the topic of movement, including through the following goals:

Children ‘make plans’

Ask questions about themselves and their environment... and look for answers

Collect different things...

Enjoy thinking about things together with others

Observe their environment closely, make assumptions and test them using different strategies

(cf. Baden-Württemberg, 2016, p. 148)

In the education and development area BODY, children expand their physical skills and abilities through targeted activities. In addition to simple movement patterns such as walking or carrying, the movement construction site also requires more complex movement patterns, which require the motor and sensory/balance organs of the child's body to work together. This includes, for example, balancing, climbing or overcoming obstacles. Here, too, goals can be derived from the educational and developmental area:

Children... and expand their scope of action and experience

Acquire knowledge about their bodies

Develop a sense of their own physical abilities and limitations as well as those of others and learn to accept them.

Develop an understanding of... regulating and maintaining the health of their bodies

Develop a positive body image and self-concept...

Develop their physical fitness and coordination skills and abilities

Expand their gross and fine motor skills and abilities

Find their own ways of developing their motor skills, even under difficult conditions

(cf. Baden-Württemberg, 2016, pp. 112–113)

Broad objectives

X. engages creatively with building materials.

X. expands her knowledge of the topic of social interaction.

X. practises gross motor movements.

Specific objectives

X. works together with other children to create a self-built object.

X. practises constructing.

X. builds together with other children in the movement construction site.

X. jumps over an obstacle.

Planning the activity

Reasons for the activity

X.'s impressions and developments were documented and recorded through everyday observations. An evaluation was carried out for the activity using Kuno Beller's development table. This yielded the following picture:

X.'s developmental age is 9.14 on average. Above the developmental age are the areas of environmental awareness (10.75), language & literacy (10.62), cognition (10.37) and gross motor skills (9.59). X.'s individual strengths can also be seen here. This is because the language & literacy area ranges between 9 (just below the developmental age) and 13. The areas of cognition and gross motor skills also range between phases 8 and 12, with the average value for cognition slightly higher than the developmental age at just under 1.5 phases above the average value than the average value for gross motor skills at 0.5 phases above the developmental age.

Below the developmental age are the areas of body awareness and care (7.46), social-emotional development (8.13), play activity (7.41) and fine motor skills (8.78). This also reveals X's individual weaknesses. The area of play activity ranges between phases 5 and 10. Social-emotional development ranges between phases 4 and 12, which is a very wide range. In the area of body care and body awareness, the phase range is also between phases 5 and 11. Here, the average value of 7.46 is below the developmental age. Fine motor skills range between phases 6 and 12, with the average value (8.78) close to the developmental age (9.14).

According to this assessment, X.'s developmental age is well below the age norm (15) at an average of 9.14. Note: Kuno Beller himself does not want this comparison to be made. Nevertheless, I am applying it. In the area of gross motor skills, a major developmental phase is currently taking place.

On the profile analysis sheet for the development of experiential activities, meaningful connections were identified for X., making a movement activity in the form of a movement construction site ideal for promoting the educational and developmental areas of senses, thinking and body (for further information, see observation with Kuno Beller). I have not yet gained any personal experience with the planned programme in the form of the movement construction site. However, I am familiar with the use of movement programmes through activities in my previous practice.

Selection of the group

Reason for the group constellation

The group was put together on the basis of emotional and social skills. Care was also taken to ensure that the characters in the group were heterogeneous. The children have no conflicts with X. in everyday life at the nursery (free play), so that ‘everyday conflicts’ can be avoided in the targeted programme. This can also lead to new connections between X. and the other children, which may lead to new playmates in the medium term.

When selecting the group, importance was also placed on ensuring that the children participating in the activity were calmer and did not display overly dominant behaviour, so as to avoid overwhelming or causing X to withdraw. This reduces the likelihood of any disruption to the activity in advance.

Description of the individual children

Child 1

First name: Y.

Gender: male

Age: 4:6

Nationality: German

Interests & topics: animals, nature, the sea, building, movement

Reason: Y. is a very loving and understanding playmate for the children. Due to his personality, he could encourage X. to engage in social activities (e.g. accepting other play ideas) during free play. Therefore, Y. fits well into the group constellation. Furthermore, Y. can motivate the other children and contribute to dialogue with his perspectives. From an educational point of view, it would therefore be desirable for X. and Y. to engage in free play together so that they can learn from each other.

Child 2

First name: Z.

Gender: female

Age: 3:9

Nationality: German

Interests: Imagination, nature, animals

Reasoning: At first glance, Z. is a rather reserved girl. However, if you give her some time and involve her, she blossoms and finds great joy in activities and imaginative stories. Due to X.'s interests and her quiet personality, Z. is a sensible addition to the group as another member of the activity.

Factual analysis

Child learning

In order to plan and implement activities, one must first try to understand how child learning actually works. However, I will not go into basic things such as general learning theories or the like here. Rather, I would like to include a brief, concise and very practical introduction to factual analysis from the perspective of cognitive development. This is because many educators today still have misconceptions about child development.

A suitable example would be a planned programme for a child. Here, I am planning an exercise programme and have set myself educational goals in this regard. These should, of course, be verifiable and should be achieved during the practical visit. So far, so good. The programme is carried out and sometimes the set goals are not achieved. This is exactly where some educators make a mistake. The correct conclusion is that perhaps the goals were set too high or perhaps the child's interests were not taken into account. Maybe the child was just having a ‘bad’ day. All of this is possible when working with people. But what is not possible is that the child has learned nothing as a result.

This is because every activity a child engages in initiates changes in nerve cells, leading to new connections. Children are constantly learning, which means that synapses are constantly being formed and remodelled. With regard to children's movement, it is important to note that children must have the opportunity to ‘grasp’ the world so that their sensory and motor skills can develop in harmony. This is a prerequisite for later abstract thinking.

Furthermore, as an educator, one should be aware that there are closing windows of opportunity for certain childhood developments. In the case of different visual performance of the two eyes (left 70% | right 100%), treatment (e.g. with an eye patch) is only possible within the first five years of life. If action is not taken within these five years, the child will become blind in one eye.

In terms of speech, this window of opportunity is 13 years, as proven by feral children, but for us in practice, this is certainly only of theoretical interest.

In the area of thinking, initial data now suggests that the development of the frontal regions of the brain is complete at around 25 years of age and can only be changed/expanded to a limited extent. It is important to know that the more a child can do, the easier it is for them to learn similar things. These previous experiences are therefore essential, which is why it is so important to initiate educational processes during this period in order to enable children to learn throughout their lives.

Another extremely important point in child learning is to pay attention to the child's enjoyment. This is because emotions are closely linked to learning. Negative experiences (fear) lead to a change in the learning situation due to the amygdala in the brain. This fear prevents creativity and thus learning. The opposite of this physical system works by releasing dopamine, which is an accelerator for rapid learning. Thus, learning with fear is possible, but it leads to a loss of creativity when later recalling and applying what has been learned (in each case) and should therefore always be avoided.

Furthermore, digital media in daycare centres are highly problematic and cause immense harm to children. They are addictive and impair brain development. (cf. Spitzer, 2018)

Movement in general

Movement can be broadly described as changes in position through space and time. This process of movement is essential for humans because, on the one hand, humans need movement resources to perform essential actions such as eating. Furthermore, humans must be able to explore nature in order to be capable of action, which is not possible without motor skills.

In the field of education, the term movement can be divided into two subgroups:

Motor skills

Encompasses all physical processes that control and regulate movement.

Psychomotor skills

Psychomotor skills deal with the unity of motor skills and psychological experience.

Ultimately, movement is also a non-verbal means of expression for an individual. (cf. Dasenbrock et al., 2020, pp. 200–202).

In order to better understand movement, we will first take a look at the physiological processes that take place in the body.

Movement from a physiological perspective

The basis of human body movement consists of the interaction of the following four levels:

Spinal cord

Brain stem

Cerebellum

Cerebrum

The spinal cord is where spinal motor function takes place. There, a low-threshold response to a stimulus occurs in the form of a reflex, which represents the lowest functional level of motor function.

The brain stem is directly connected to the spinal cord and has contact pathways to higher brain regions. The medulla oblongata acts as an extension of the spinal cord. Together, they serve as the control centre for motor function through control and modification. There are also brain stem reflexes, which enable rapid adaptation to changing environmental influences.

The following reflexes are essential for movement:

Static reflexes: Holding and positioning reflexes for correct posture in space

Statokinetic reflexes: Reflexes triggered by movement to maintain balance.

The cerebellum receives information from the labyrinth, spinal cord and movement plans from the motor cortex. Here, the pars intermedia corrects planned slow movements of the motor cortex and controls the target and support motor functions. The cerebellum also contains the cerebellar hemispheres, which create movement programmes for rapid target movements based on information from the associative cortical areas of the movement plans designed by the cerebrum.

The cerebrum consists of various cortical areas. The motor cortex is the highest functional level of motor function. It receives information from the aforementioned subordinate brain regions. It processes this information and ultimately issues the command to execute the movement. (cf. Lecturio GmbH, 2021).

Once you know the most basic principles of how movement is generated, the next step is to address possible physical limitations in movement.

Limitations of movement

A healthy body basically has all the organs necessary to generate and transmit movement signals. Furthermore, the organism is capable of executing the desired movement. However, especially nowadays, with the keyword of inclusion, educators are increasingly dealing with children who have physical or other limitations.

I will therefore briefly list possible diseases of the musculoskeletal system in childhood:

Paraplegia

Malpositions of the musculoskeletal system

Infantile cerebral palsy

Motor development delays

Juvenile chronic arthritis

Peripheral paresis

Spina bifida

Asymmetries such as torticollis

Scoliosis

Bone fractures

This list is a small and non-exhaustive insight into the wide variety of possible movement restrictions.

You are probably wondering why I am listing these and why educators should have heard of them at least once. After all, educators do not make diagnoses or treat these conditions. In my view, however, this cannot be seen in such a simplistic way. As mentioned earlier, the topic of inclusion is becoming increasingly important. Furthermore, educational professionals have to work together with other disciplines such as medicine, speech therapy and physiotherapy. After all, if a child with motor impairments spends 40 hours a week at the facility, for example, that is a very long time. In addition, orthopaedic measures usually have to be implemented throughout the day and therefore do not stop when the nursery day begins in the morning.

But before educators can think about implementation in everyday nursery life, the next step is to first address the basics of movement in early childhood.

Movement in early childhood

Children have an instinctive and early recognisable urge to move. This urge to move helps children discover themselves and the world. We can use this urge to move to get children excited about exercise. Only by starting to maintain and promote the urge to move in young children can we bring about a long-term positive change in the general exercise behaviour in our society. It is well known that exercise contributes to healthy physical, mental and psychosocial development. (cf. Kersch, 2020, p. 3)

Basic motor skills

From as early as the eighth week of pregnancy, a foetus practises simple movements. By the tenth week of pregnancy, even more complex movements such as hand movements leading to the mouth occur. These movements are spontaneous and not reactions to external stimuli. Nevertheless, such movement patterns at such an early stage of development are remarkable.

After birth, motor skills continue to develop at a remarkable pace during the first years of life. After about three months, the child can already move its head against gravity and hold it steady (head control). The first attempts at grasping are made and motor skills are now slowly becoming more and more oriented towards personal goals. After six months, the baby is already able to lie symmetrically on its back. Furthermore, most babies of this age can already support themselves with their hands and forearms. In terms of fine motor skills, they can now usually grasp objects with a radial fist grip and pass an object from one hand to the other along the midline.

From the 12th month onwards, the transition from baby to toddler age takes place. Most toddlers can sit upright with a straight back from this age onwards and have already developed stable balance control for this. Toddlers also begin to change position from lying on their stomach to lying on their back and back again. Dexterity increases and toddlers can usually use the scissor grip.

At 24 months, most toddlers can already pick up objects from the floor while standing. They practise walking up stairs step by step as well as holding onto the banister or adults. They have now mastered the pincer grip and usually start painting with a fist grip.

From 36 months onwards, children usually begin to hop successfully with both legs and move quickly with the help of their arms. They are also usually able to avoid obstacles and stop quickly. When discovering books, children can now turn individual pages correctly with the help of a precise 3-finger pincer grip. (cf. Schlack, 2012)

Visual impairment and motor development

Blindness in childhood has nothing to do with absolute blindness. Rather, it also includes children who still have some visual ability. A blind child can often still recognise light/dark contrasts or the outlines of people and objects. For these reasons, early intervention is also an immensely important prerequisite for the best possible development of every child with visual impairments.

Referring back to the beginning of the factual analysis, we have already established that people explore nature in order to be able to act, and that motor development is essential for this. However, visually impaired children, and especially blind children, develop differently from sighted children. This is because the stimuli from the environment are reduced to the optic nerve or, in the case of blindness, are usually completely absent. As a result, children with visual impairments are less or not at all motivated to reach for nearby objects or to move towards an object in a targeted manner.

In a longitudinal study, for example, a total of 107 individual skills from four areas of development (manual-practical, gross motor, social-interactive and linguistic) were compared between four children born blind and sighted children. The study showed that blind and sighted children did not develop in parallel, but diverged. Only minor differences were found in language skills. (cf. Brambring, 2005)

It can therefore be concluded that visually impaired and blind children may need support, particularly in the development of gross and fine motor skills, and that this must be kept in mind. It is always important to note that visually impaired and blind children need a great deal of physical closeness in order to have direct and ‘connectable’ experiences.

In addition to verbal communication, this physical, tangible closeness is of existential importance, especially for blind children, as it allows them to perceive their caregivers and explore from this secure base.

Visual impairments often occur alongside other disabilities and abnormalities. For these so-called multiple disabilities, physical closeness to a caregiver is also an essential prerequisite for mobility or changing position. (cf. Sarimski & Lang, 2020, p. 24ff.)

Furthermore, the contrast ratio should also be taken into account, especially if minimal vision is still present. There is a simple trick you can use for this. Take a photo of the situation and use the black and white filter.

This allows the contrast ratios to be displayed more clearly. This is also illustrated by the following photos:

Psychomotor skills

There are different approaches and theories regarding the importance of movement. The following are particularly noteworthy:

Tamboer had an anthropological view of the significance of human movement. Herr von Weizsäcker, on the other hand, had a Gestalt theory perspective. Jean Piaget viewed movement from a developmental psychology perspective (knowledge) and Erikson from a psychosocial perspective (identity). So everyone has a different view of the word movement.

This is not surprising, as the word psychomotor skills encompasses the following six areas, which underline the broad scope of psychomotor skills:

Self-competence

Body awareness

Material awareness

Technical competence

Social experience

Social competence

Psychomotor skills are thus characterised by a combination of perception, experience, movement and action. The focus is therefore not on individual areas of development, but on the further development of a child's entire personality through movement. Only when perception and movement are understood as a single entity can we move away from the idea of promoting perception as pure sensory training. Motor skills development is therefore a multidimensional discovery and must be taught in holistic action situations.

Such action situations should be designed as problem-solving tasks that allow children to act creatively. It is therefore not useful to simply follow predefined solutions. (cf. Eckloff)

In order to do justice to these scientific findings, the movement programme takes place as a movement construction site.

The movement construction site

The basic concept of the movement construction site was developed in 1983 by Klaus Miedzinski. To this day, the concept has continued to evolve, but has always remained true to its core: to encourage children to move around in large spaces. There are also links to Maria Montessori's approach, as the movement construction site is ultimately a prepared environment that encourages children to explore.

The movement construction site offers children the opportunity to actively engage with materials and their properties. They can try out and test new possibilities according to their own imagination. Here, individual children quickly become aware of their physical limits, so that joint efforts in movement experiments lead to movement safety and self-confidence. All of the reasons mentioned so far speak against a prepared movement landscape and thus in favour of an educational offer with a movement construction site.

Moreover, a movement construction site offers much more than just physical activity when it comes to achieving the playful goal. Children practise creativity, live out their fantasies and implement ideas. In doing so, they learn about theories and physical laws. Ultimately, children manage to achieve their goals through inventiveness, experimentation and courage. (cf. Miedzinski & Fischer, 2014, pp. 13–15)

Another important aspect is perceptual-experiential skills. The exploratory type of meaning extends in three ways:

Physical experience

Material experience

Social experience

It is important to know and understand that movement not only serves as a medium for social experience, but also lays the foundation for social relationships. Thus, opportunities for movement in a group are a perfect communication tool and learning environment, and this is where their special educational significance lies. (cf. Miedzinski & Fischer, 2014, pp. 32–33)

Methodological and didactic planning

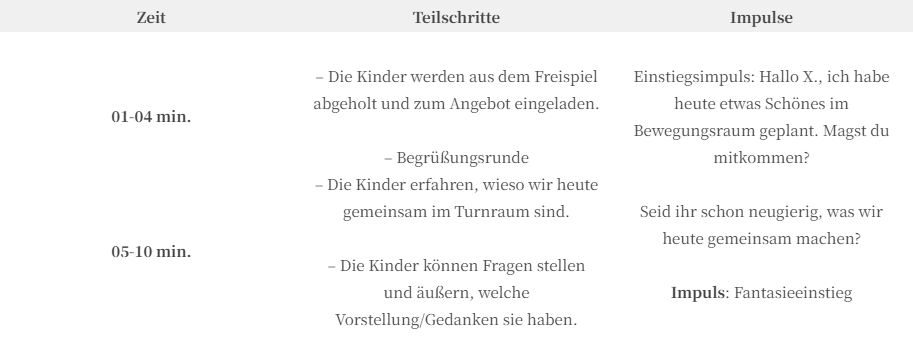

Schedule

Introduction

The introduction takes into account the methodological and didactic principles of the step-by-step approach and the principle of activity. No specific objectives are set at this stage.

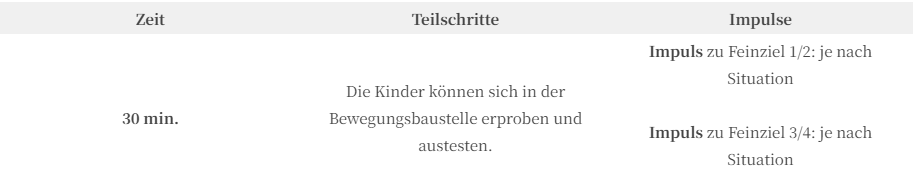

Main section

The main section applies the methodological and didactic principles of the exercise as well as the principle of activity. Specific objectives one, two, three and four are integrated.

Conclusion

The conclusion applies the methodological and didactic principles of the exercise and the principle of activity.

Anticipating problems

A child does not want to participate in the activity

If a child does not want to participate in the activity, that is fine. The child will remain in the free play area of the group room.

A child is ill and does not participate

It may be that a child is ill on the day of the activity and is absent. In this case, another child can take their place, but care must be taken to consider the group constellation when making the selection. Only a child with a similar character and cognitive development level should be considered.

A child is not playing by the rules

If a child repeatedly disturbs the other children while they are building, they can alternatively sit at the edge of the room and wait there until the end of the activity. If they continue to disturb others there, they can go back to the group room with the instructor and continue playing there during free play.

The children are/become bored

If the children become bored at the movement construction site, I can redirect their interest back to the movement construction site with targeted stimuli.

A child no longer wants to play at the movement construction site

If a child no longer wants to play at the movement construction site, it depends on the situation. If they are playing a different game and not disturbing the rest of the group, an attempt will be made to bring the child back with appropriate prompts. However, if they are causing a disturbance, the procedure under point 3 will be followed: A child is not playing by the rules.

A child injures themselves

If a child injures themselves at the movement construction site, it depends on the severity of the injury. In the case of minor injuries, we wait to see how the child and the group react to the situation. Only if the children are unable to resolve the situation themselves do I intervene as a qualified childcare professional.

Preparatory activities

Room planning

The movement room was chosen as the venue because it offers the necessary space and is designed for gymnastics and movement activities. It has wall bars, ceiling hooks, different floor materials (mats, foam blocks) and other stable and usable equipment. It offers a wide range of construction and discovery opportunities, especially for the planned movement construction site.

Below is a diagram of the movement room with the planned movement construction site:

Preparing the room

The diagram above shows the safety measures for the bench. If necessary, the room can be ventilated through the windows on the left (not visible). There is also a bench there. The instructor and the practical teacher can observe the activity from here.

Room, materials and media list

Movement room

Imagination for a short introductory activity

Blanket(s) as a boat for the introductory activity

Bench

3 thin blue mats

2 thick blue mats

Building blocks of various types

Additional materials, depending on the situation

Bibliography

Baden-Württemberg, M. f. K. J. u. S. (2016). Orientation plan: For education and upbringing in Baden-Württemberg kindergartens and other childcare facilities (2nd ed.). Herder.

Brambring, M. (2005). Divergent development of blind and sighted children in four areas of development. Journal of Developmental Psychology and Educational Psychology, 37(4),

173–183.

Dasenbrock, F., Dietrich, D., Fröhlich, C., Herrmann, U., Hoffmann, S., Kessler, A., Kreuels, A., Perret, D., Reinecke, M., Rosche, M., Ruff, A., Schmitt, C., Seidel, W., Wagner, F.,

Weber, U. & Witzlau, C. (2020). Educators Volume 2: Professionally designing social-educational work (2nd ed.). Cornelsen.

Eckloff, G. The importance of exercise for childhood development. Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg,

Kersch, D. (2020). Handbook on promoting physical activity in children aged 0-12. https://gouvernement.lu/dam-assets/documents/actualites/2021/01-janvier/Bewegungsforderung-bei-Kindern-0-12.pdf

Lecturio GmbH (Ed.). (2021, 9 December). Motor skills: Everything you need to know about the basics of movement and motor systems. https://www.lecturio.de/magazin/grundlagen-motorik/

Miedzinski, K. & Fischer, K. (2014). The new movement construction site: Learning with your head, heart, hands and feet; Model for movement-oriented development support (3rd ed.). Borgmann Media.

Sarimski, K. & Lang, M. (2020). Early intervention for blind children: Fundamentals for working with blind children and their families (1st ed.). Bentheim: Vol. 1. edition bentheim.

S. Beller: Kuno Beller's Development Table 0-9, 10th completely revised and expanded edition

Schlack, H. G. Prof. Dr. (2012). Motor development in early childhood. University of Bonn.

Spitzer, M. Prof. Dr. Dr. (2018, 20 March). School of the future: Education for a fulfilling life. Vulkan TV, Feldbach. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NR-KPZEL3Aw